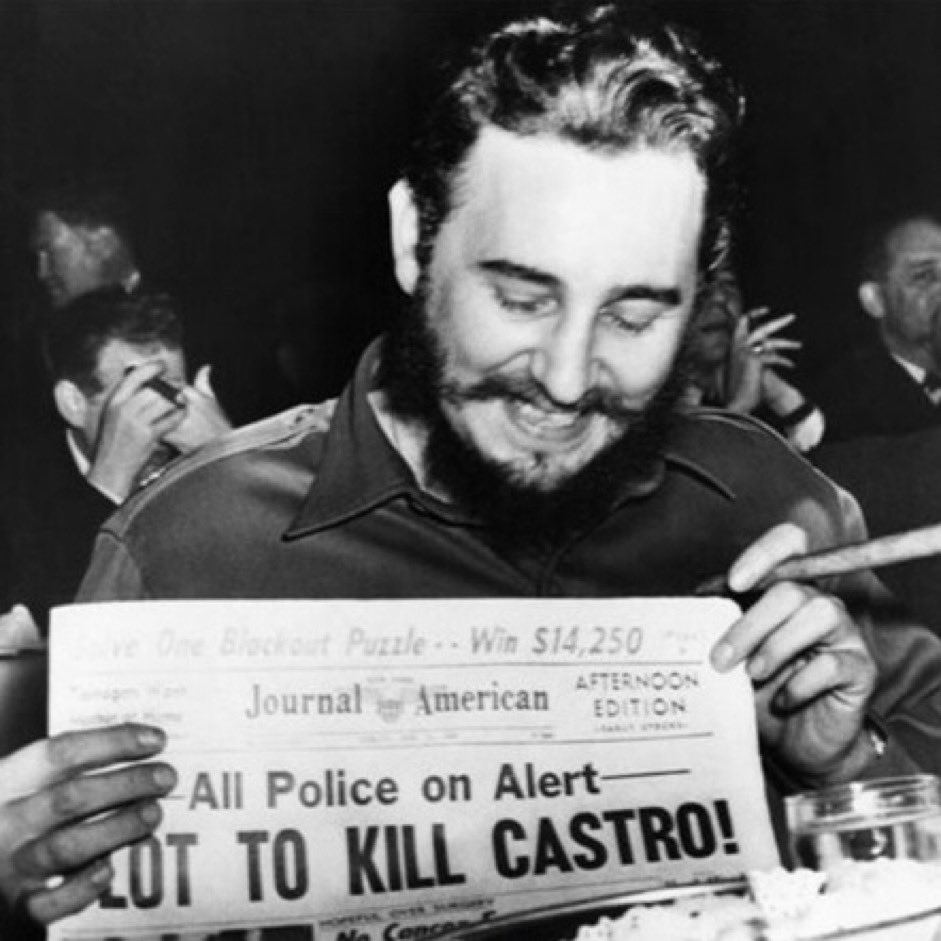

Fidel Castro. The infamous dictator. How did he evade a supposed 638 assassination attempts by the CIA?

Fidel Castro, the enigmatic Cuban leader, casts a long shadow, even in death. One aspect of his life that continues to captivate and perplex is the staggering number of assassination attempts he allegedly faced: a whopping 638, according to his former secret service chief. But is this figure a badge of his survival prowess or a case of inflated numbers?

Fidel Castro, the Cuban revolutionary, was known for his charismatic leadership and long-standing rule. He transformed Cuba’s political landscape, implementing socialist reforms and challenging the influence of the United States in Latin America

. His lengthy tenure and resilience made him a polarizing figure globally, revered by some for his efforts in social reform and criticized by others for his authoritarian governance style. Castro’s charisma and unwavering commitment to his ideals left an indelible mark on Cuban history and international politics.

The source of the 638 claim lies in Fabian Escalante’s book and subsequent documentary, both named “638 Ways to Kill Castro.” Even a Cuban state TV miniseries took inspiration from this seemingly unbelievable number. However, it’s crucial to remember that this originates from a single source within the Cuban government, albeit a high-ranking one. This lack of independent verification raises an important question: can we truly trust this figure?

A more objective perspective comes from the 1975 Senate Church Committee investigation, aptly named “Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders.” Their findings reveal a far less dramatic picture. The committee documented only eight CIA-involved plots against Castro between 1960 and 1965. And even these often didn’t materialize, remaining in the realm of “schemes” rather than concrete attempts.

Interestingly, the discrepancies don’t end there. In 1975, Castro himself presented a list of only 24 CIA assassination attempts to Senator McGovern. Why the sharp drop from the 336 attempts he claimed publicly a few years earlier? And when the CIA countered Castro’s list, only nine incidents showed even remote connections to them, with the rest involving unrelated individuals.

Unraveling the truth seems further complicated by the inclusion of “schemes” and “character assassination” plots in the 638 figure. Additionally, attributing some of these plots to Cuban rebels, potentially acting as CIA proxies, muddies the water further.

Weighing the evidence, I find it challenging to swallow the claim of 638 attempts uncritically. While a handful of genuine CIA plots existed, a figure averaging over one attempt every three weeks for 42 years seems improbable. Such constant and unsuccessful operations paint an improbable picture of the CIA’s competence in handling sensitive and complex missions.

On the other hand, the Church Committee’s rigorous investigation, still acknowledged for its thoroughness, found only limited CIA involvement. Attributing more faith to their findings than a single, unverifiable source seems more prudent.

The number 638 remains a captivating enigma, more likely a product of propaganda and inflated claims than a factual record. While Castro certainly faced some genuine threats, the true extent of assassination attempts paints a far less sensational picture. Ultimately, this story underscores the importance of critical thinking and independent verification when navigating the murky waters of historical claims, especially those coming from single, potentially biased sources.

Civil Service Announces 2024 Online Examination Details for Graduate Applicants

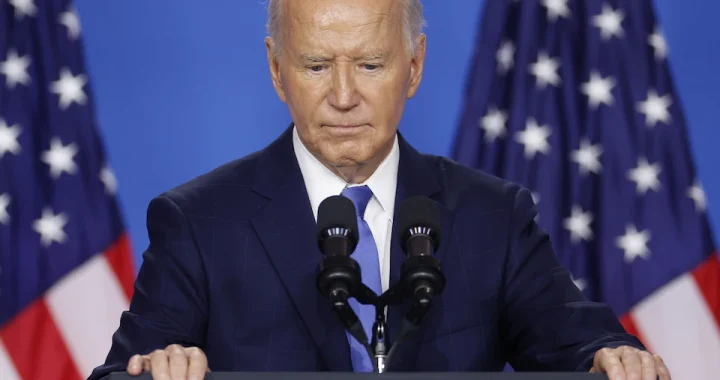

Civil Service Announces 2024 Online Examination Details for Graduate Applicants  BREAKING: President Biden Announces Decision Not to Seek Reelection

BREAKING: President Biden Announces Decision Not to Seek Reelection  Real Reason Behind the Appointment of Yohunu as Deputy IGP

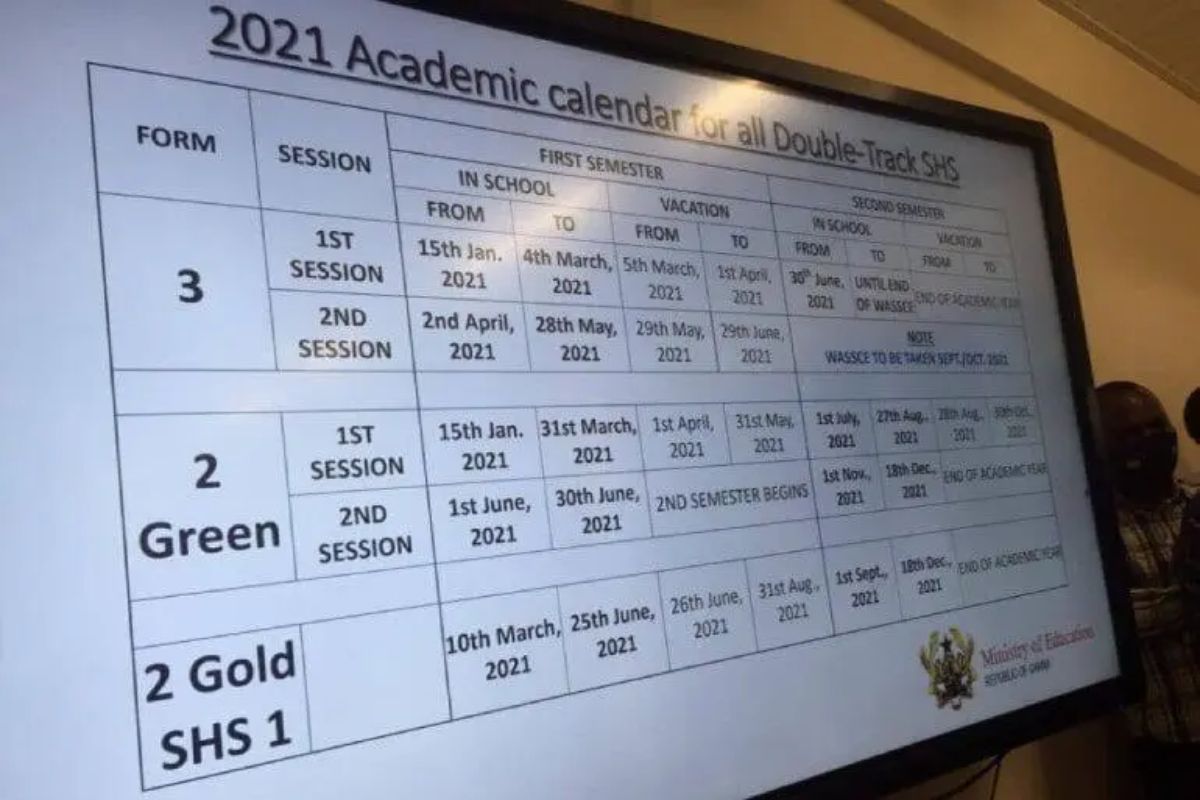

Real Reason Behind the Appointment of Yohunu as Deputy IGP  GES 2024-2025 Academic Calendar for Public Schools

GES 2024-2025 Academic Calendar for Public Schools  GES to recruit university graduates and diploma holders-GES Director General

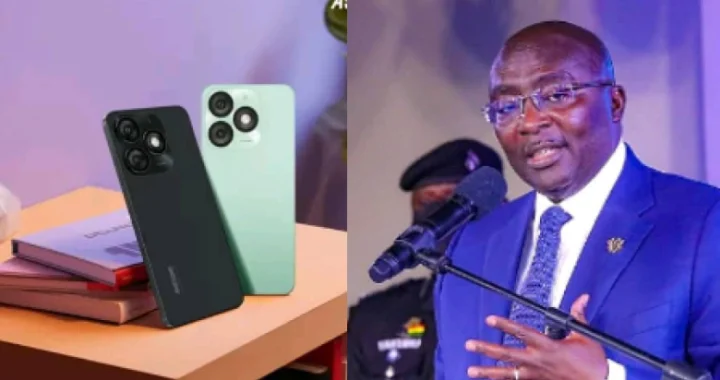

GES to recruit university graduates and diploma holders-GES Director General  Dr. Bawumia’s Smart Phone Credit Will Take 125 Years To Repay: A Misleading Promise

Dr. Bawumia’s Smart Phone Credit Will Take 125 Years To Repay: A Misleading Promise  GES is expected to announce reopening dates for public schools today

GES is expected to announce reopening dates for public schools today