Hasidic School Is Breaking State Education Law, N.Y. Official Rules

New York State officials have determined that a private Hasidic Jewish boys’ school in Brooklyn is violating the law by failing to provide a basic education, a ruling that could signal profound challenges for scores of Hasidic religious schools that have long resisted government oversight.

The ruling marks the first time that the state has taken action against such a school, one of scores of private Hasidic yeshivas across New York that provide robust religious instruction in Yiddish but few lessons in English and math and virtually none in science, history or social studies.

It also served as a stern rebuke of the administration of Mayor Eric Adams, whose Education Department this summer reported to the state that, in its judgment, the yeshiva was complying with a law requiring private schools to offer an education comparable with what is offered in public schools.

The decision, issued last week by the state education commissioner, Betty Rosa, stemmed from a 2019 lawsuit brought by a parent against the school, Yeshiva Mesivta Arugath Habosem, which enrolls about 500 boys in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

A spokesman for the New York City Department of Education said the city conducted a thorough investigation of the school, visiting multiple times, reviewing instructional materials and interviewing staff members.

“We stand by our investigation and recognize that our recommendation was just that — a recommendation — and that the state had ultimate authority to make the determination,” said the spokesman, Nathaniel Styer.

The potential ramifications of Ms. Rosa’s decision extend beyond a single school. The ruling could be a harbinger of significantly tougher oversight of Hasidic yeshivas, and could open the door for lawsuits or complaints about other schools.

“The state did right,” said Beatrice Weber, a mother of 10 who brought the suit against her youngest child’s school and has since left the Hasidic community. “Hopefully now things will actually change.”

The ruling came a month after the The New York Times reported that more than 100 Hasidic boys’ schools in Brooklyn and the lower Hudson Valley have collected at least $1 billion in taxpayer money in the past four years, but many have denied students secular instruction.

Timeline: New York’s Oversight of Hasidic Schools

State law requires all private schools to provide an education comparable to what is in public schools. In 2015, New York City’s education department said it would investigate complaints about the quality of secular education in schools in the Hasidic Jewish community. Here’s a timeline of the investigation:

The Times found that Hasidic boys’ yeshivas that administer state standardized tests perform worse than any other schools in New York State, and that religion teachers in many of the schools have frequently used corporal punishment to enforce order, hindering learning.

Ms. Rosa’s decision will also provide the first test of a new set of state rules aimed at regulating private schools, which have largely been allowed to operate without oversight for decades. Those regulations, which went into effect two weeks ago, hold that schools that do not follow state law could lose their public funding.

Hasidic leaders fought to block the new rules before they were approved by the State Board of Regents last month, casting them as a dire threat to the community. Earlier this week, a group of yeshivas and their supporters sued New York education officials over the rules in state court. Many of the plaintiffs in the suit were non-Hasidic yeshivas that provide extensive secular education and would likely not be affected by the regulations.

“Yeshivas are the central and irreplaceable pillar of the Orthodox Jewish life in New York,” reads the lawsuit, which seeks to have the regulations overturned.

On Wednesday, a spokesman for one of the groups that filed the lawsuit, the Parents for Educational and Religious Liberty in Schools, defended Yeshiva Mesivta Arugath Habosem.

“Educators from the city’s Department of Education visited the school several times and determined that it met the substantial equivalence standard,” said the spokesman, Richard Bamberger, referring to the state law. “It is disappointing that political appointees at the state education department won’t accept the city’s findings.”

In her ruling, Ms. Rosa sharply criticized the city’s oversight of the school, saying that its own inspections of the yeshiva did not support its conclusion that the school was providing an adequate education.

She said that observations she received from city officials in fact indicated that the yeshiva does not offer sufficient instruction in English, social studies or science. The school’s math instruction appeared to be better but was still not on par with what is offered in public schools, Ms. Rosa said. The commissioner wrote that the yeshiva administers state tests in English and math, but she added that the “vast majority” of its students failed the exams and scored much lower than the average student in city public schools.

The commissioner also wrote that the school declined to allow a visit that state education department officials requested last month and repeatedly declined to provide evidence that it was complying with state education law, even after Ms. Rosa warned that there was insufficient proof that the school was in compliance.

Beyond finding fault with the city’s inspection of the Brooklyn school, the ruling also raises questions about City Hall’s willingness to intervene in Hasidic schools. Mr. Adams has long enjoyed the political support of the Hasidic Jewish community, which tends to vote as a bloc.

In response to the Times investigation, he said that his administration would complete an inquiry into dozens of schools that was started under former mayor Bill de Blasio in 2015 but was put on hold amid the pandemic. In 2019, an interim report found that only two of 28 Hasidic yeshivas the city had visited were complying with state education law.

“People understand that this is outside the purview of the governor,” Ms. Hochul said last month when asked about the Times investigation into Hasidic yeshivas.

The governor was endorsed by Hasidic groups ahead of the Democratic primary this summer, and one group wrote on Twitter that the governor had promised a hands-off approach to the yeshivas in a post that was deleted soon after.

Many Hasidic groups have not yet endorsed a candidate in the general election. Representative Lee Zeldin, the Republican candidate for governor, has sought to capitalize on the Hasidic community’s outrage over increased government oversight into the yeshivas.

Some Hasidic leaders have openly declared that they would never change how their schools operate.

Ms. Weber’s 2019 lawsuit against her son’s yeshiva represented a major challenge to the Hasidic community.

The school at the center of her complaint, Yeshiva Mesivta Arugath Habosem, is a longstanding institution in the community with a reputation for providing more secular education than many other Hasidic boys’ schools.

Nevertheless, a Times analysis of state test score data available for three grades at the school showed that while 122 students took reading and math exams in 2019, just one of them passed.

Records obtained by The Times showed that the school received about $4.5 million in government funding in the last full year before the pandemic.

In her complaint, Ms. Weber alleged that her then-6-year-old son, Aaron, had yet to receive any secular education. She also said that materials from the school indicated that students who received English-language instruction only got it for about 90 minutes a day, four days a week.

Ms. Weber filed a petition with the state education department asking Ms. Rosa to intervene. The commissioner dismissed the petition in 2021, citing a lack of jurisdiction. But Ms. Weber successfully challenged that decision in state court, securing a judge’s order that the state issue a final determination on her son’s school.

As the state prepared to make its ruling, city officials filed their required recommendation in July. In saying they believed the school was complying with the law, officials said they had observed English-language instruction, including in social studies, on topics like time zones and the U.S. Postal Service, and in science, on subjects like hurricanes and satellites, according to a copy of their report obtained by The Times.

That is more instruction in those areas than is typically provided in Hasidic boys’ schools, records and interviews show.

City officials also said in the report that the school’s Judaic studies curriculum taught additional key skills.

“No longer can a Hasidic yeshiva use its Jewish studies program to argue that through such parochial studies it is complying with the state’s education law,” Mr. Shapiro said, adding: “This is an historic, brave and correct determination.”

Ms. Weber, who was recently named executive director of Young Advocates for Fair Education, a group that has pushed for more secular education in Hasidic yeshivas, has spent years sounding alarms about deficiencies in Hasidic boys’ schools.

On at least one occasion, she showed up at the school to observe classroom instruction, but said she was asked to leave the building after 45 minutes.

Her filings also cited letters written by the rabbi in charge of the school’s English department that displayed an apparent lack of fluency in English.

“Bus changes can only be made in the office of Transpiration,” the rabbi wrote in a 2019 letter. Elsewhere, he added: “Any misbehavior will be dealt with in a firm manor.”

Source: nytimes.com

Send Stories | Social Media | Disclaimer

Send Stories and Articles for publication to [email protected]

We Are Active On Social Media

WhatsApp Channel: JOIN HERE

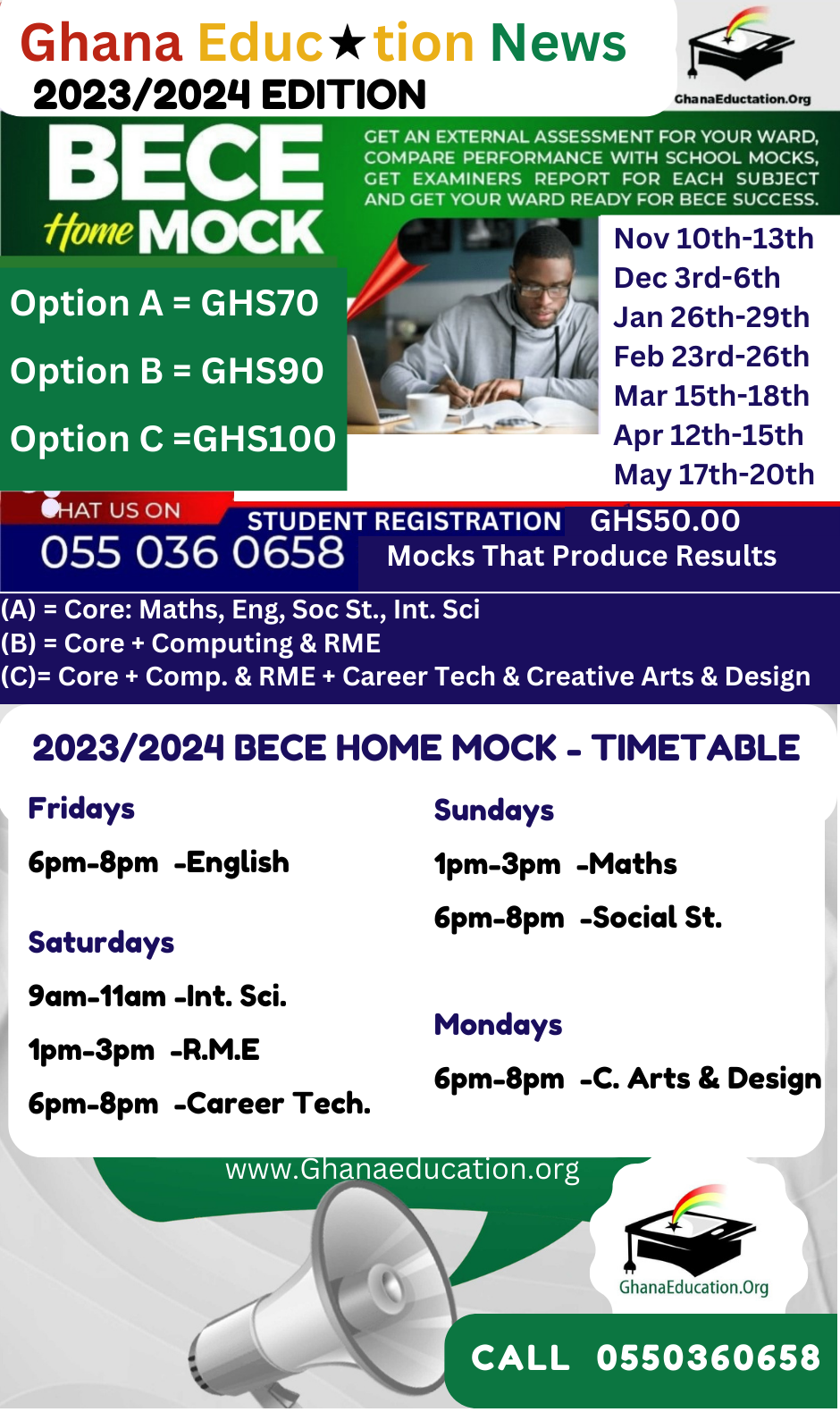

2024 BECE and WASSCE Channel - JOIN HERE

Facebook: JOIN HERE

Telegram: JOIN HERE

Twitter: FOLLOW US HERE

Instagram: FOLLOW US HERE

Disclaimer:

The information contained in this post on Ghana Education News is for general information purposes only. While we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the post for any purpose.

List of WAEC Offices and Contacts Across Ghana

List of WAEC Offices and Contacts Across Ghana  La District Junior Youth 2024 BECE Mock: Ghana Education News partners the Presbyterian Church

La District Junior Youth 2024 BECE Mock: Ghana Education News partners the Presbyterian Church  WAEC Releases 2024 WASSCE Timetable (waecgh.org)

WAEC Releases 2024 WASSCE Timetable (waecgh.org)  Odomase sub chief donates US$2,000 worth computers to alma mater

Odomase sub chief donates US$2,000 worth computers to alma mater  Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Foundation collaborates with Newmont Ghana to build Artificial Intelligence Center at Kona

Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Foundation collaborates with Newmont Ghana to build Artificial Intelligence Center at Kona  Esther Cobbah elected President of Institute of Public Relations, Ghana

Esther Cobbah elected President of Institute of Public Relations, Ghana  GES grants SHS students break for voter registration

GES grants SHS students break for voter registration